The global energy sector faces a myriad of challenges, and significant change, as various governments worldwide react to the clear and present danger presented by climate change. Amidst this, significant opportunity presents itself, too.

According to Dave OudeNijeweme, global senior director for Battery Materials at Worley, “the move to limit global CO2 emissions requires a complete re-wiring of the energy system. Climate change is driving governments around the world to act.”

For the battery market specifically, where demand continues to rocket due to the global boom in electric vehicles (EVs) in recent years, “opportunities for battery material producers are substantial,” says OudeNijeweme. In the UK, for example, in November 2020, the British Government’s 10-point plan for a green industrial revolution, included an announcement that the sale of new petrol and diesel cars would be phased out by 2030 and that all new cars and vans would be zero emission by 2035. This, and other similar legislation across the world has seen the batteries market predicted to become a US$ 410bn business by 2030, according to McKinsey & Company.

“With governments keen to protect national interests, jobs, and economic growth, they are both increasing support for domestic industries and introducing new legislation,” says OudeNijeweme.

Much of the race to grab a slice of the burgeoning battery market centres on the construction of gigafactories – huge battery facilities producing battery packs to support the EV sector on an industrial scale. While the recent failure of the Britishvolt plant in the UK shows that this is by no means a silver bullet for capitalising on such rapid growth, there are still more than 300 gigafactories under construction worldwide. More than 200 are in China, however – a stark warning to Western nations that they have fallen behind in this market.

Far-reaching policy and counter policy

In the US, there has been in an unprecedented attempt to wrestle back some control of the market. President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which will see massive investment into domestic energy production while promoting clean energy, will have major ramifications on EVs and batteries – specifically in relation to critical mineral and battery component requirements. According to Goldman Sachs, the IRA effectively lowers the US domestic battery cost curve by US$45/kWh.

As OudeNijeweme outlines, although (important) details are still emerging it seems that starting now until January 2024, automakers are required to demonstrate that 40% of the extraction or processing of critical minerals occurs in the US, or a country that has a free trade agreement with the US. In addition, 50% of the value of battery components in an EV vehicle need to be manufactured or assembled in North America. Both percentages will increase over time.

Inevitably, while some Chinese companies will seek to invest in the Americas in order to capitalise on this, investing directly in the US remains difficult. A key pillar of the IRA is, intentionally, to “reduce the US’s dependence on China,” says Energy Monitor’s Nick Ferris. “Investments in US EV battery manufacturing have already ballooned as a result: some $73bn in planned US battery plants were announced in 2022 alone, according to consultancy Atlas Public Policy. US EV battery manufacturing will be 20 times greater in 2030 than in 2021, projects the US Department of Energy,” he says.

“The US battery sector is booming hand-in-hand with the EV sector. Major US EV investments in 2022 included more than $10bn – and 11,600 new jobs – across two Hyundai facilities in Georgia to manufacture EVs and batteries; more than $6bn of EV and battery investment across two General Motors facilities in Michigan; and further investments from Ford, Toyota, Vinfast and Honda, collectively worth more than $10bn, to create more than 15,000 jobs, according to data from the US Center for Automotive Research that was shared with Energy Monitor,” says Ferris.

The EU strikes back

Europe’s response to the IRA is the European Commission’s Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA). On 1 February 2023, the European Commission published its Green Deal Industrial Plan, with the aim of turbocharging the competitiveness of EU net zero industries. A joint-debt-funded ‘European Sovereignty Fund’ to subsidise green businesses across the EU was bolstered with a ‘Net-Zero Industry Act’ to provide a simplified regulatory framework for the production of technologies deemed vital for meeting/exceeding climate goals, including solar, wind, batteries, heat pumps and carbon capture and storage.

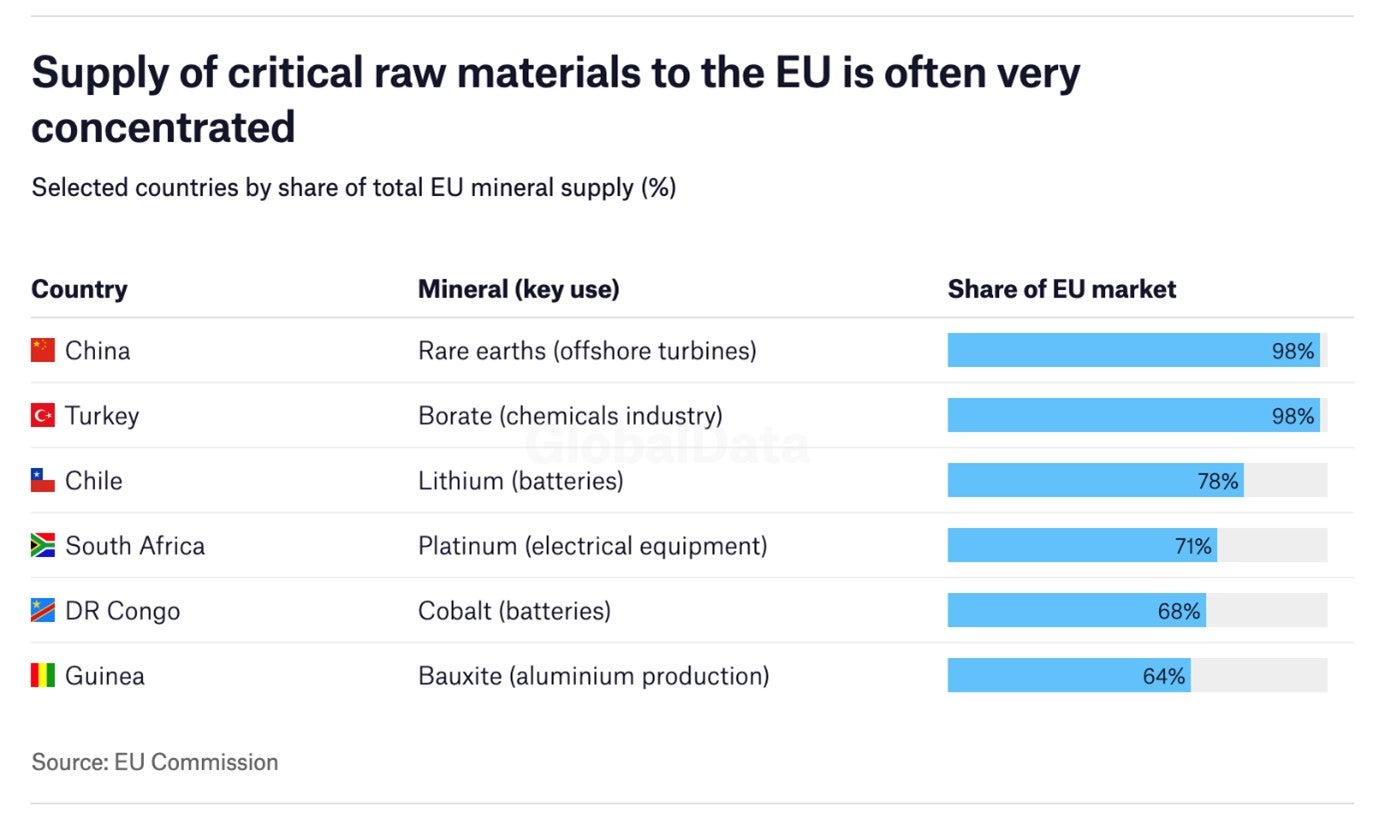

In Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s State of the Union address in September 2022, she summarised the ambition by stating that the essential raw materials for producing today’s electric vehicle batteries, such as lithium, nickel, graphite cobalt and copper are already replacing gas and oil at the heart of our economy. By 2030, our demand…will increase fivefold. And this is a good sign, because it shows that our European Green Deal is moving fast. The not so good news is – one country dominates the market. So, we have to avoid falling into the same dependency as with oil and gas.”

Energy Monitor’s Dave Keating adds wider context: “The World Bank predicts that there will be a 500% increase in demand for critical raw materials between now and 2050, and this will cause price spikes and a global supply race. One clean technology that is heavily dependent on critical raw materials is batteries. Lithium prices already saw a recent price spike of 400% between May 2021 and May 2022, according to the World Bank.

Worldwide, China is the largest exporter of 19 of the 30 critical raw materials determined by the EU as being the most vital. Those materials are, however, also found in many other countries, including within the borders of the EU itself, while other countries, “such as Indonesia, Australia, Canada, and Chile – with significant resources like nickel, copper and other valuable raw materials – are keen to grab more of the value add, with a recent example being Chile’s proposal to nationalise their lithium industry,” says OudeNijeweme.

In the EU, the new battery legislation set minimum recovery rates and minimum quantities of recycled content for new cells that increase over time. “A carbon threshold is also expected to be introduced as early as 2027, helping the European Union to produce greener batteries and cleaner transport. It also includes measures – such as a battery passport – to demonstrate where the materials come from and the embedded carbon they contain from 2024,” says OudeNijeweme, who also believes the battery passport will likely become widely legislated, including in the US, in the future.

Actions speak louder than words: Investment and the standardisation solution

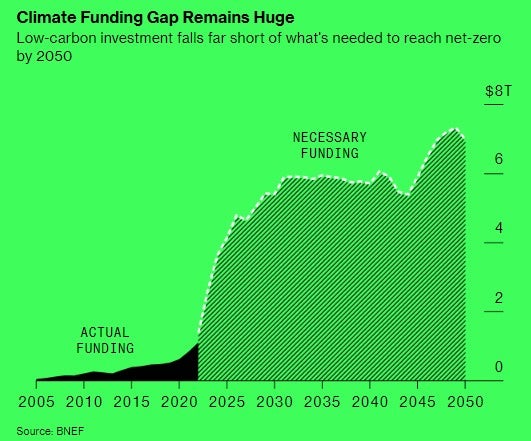

2030 is fast approaching. In this critical decade of action, net zero is our collective imperative. But what will it really take to move the world to net zero? Authored by Worley and Princeton University, the paper looks at five shifts that energy, chemicals and resources companies can use to trigger tangible change. For the batteries industry, Shift 3: Standardisation is one solution which should be explored at pace. But first, investment needs to catch up.

Source: https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2023-green-tech-startups-bnef-pioneer-award-winners/

While capital exists in principle ($41.8 trillion in global equity trading as recently as 2021, according to the Statista Research Department in February 2023 for example), it still falls short when we consider what’s necessary to reach net zero. Capital also needs to be better deployed across engineering and construction in order to deliver innovations and assets that have a pace in a net zero world.

Standardisation is the consistent solution

But as with all these new types of initiatives, technology is frequently too far ahead of the infrastructure that is needed to deliver it – including the manufacturing plants required.

For the battery market, for instance, the number of pre-cursor, active material and recycling facilities – plus the investment required to feed the demand for EVs – is significant.

Standardisation is the consistent solution, says OudeNijeweme.

“Designing one, and then building many identical facilities is an obvious answer to this challenge. Concepts exist that would enable the battery materials industry, and therefore the world, to transition to an electrified future more quickly. But this is not without its own set of challenges to standardise what are extremely complex and large-scale processing facilities. Benefits of a ‘design one, build many’ approach include lower overall capital investment levels, increased speed to market, and easier operation and maintenance. We expect new technology to lower operating costs and enable easier upgrades. And all this translates into lower investment risk,” he says.

Crucially, increased standardisation and more efficient, strategic planning “frees up precious engineering, construction and supply chain capacity; enabling a significantly faster transition to a sustainable future,” says OudeNijeweme.

A further reminder to governments and industry alike that both the urgency and solutions to address the “complete rewiring of the energy system” a sustainable transformation demands are not lacking when the right experts are consulted.

Further details:

For more information on this topic, download the whitepaper from Worley.