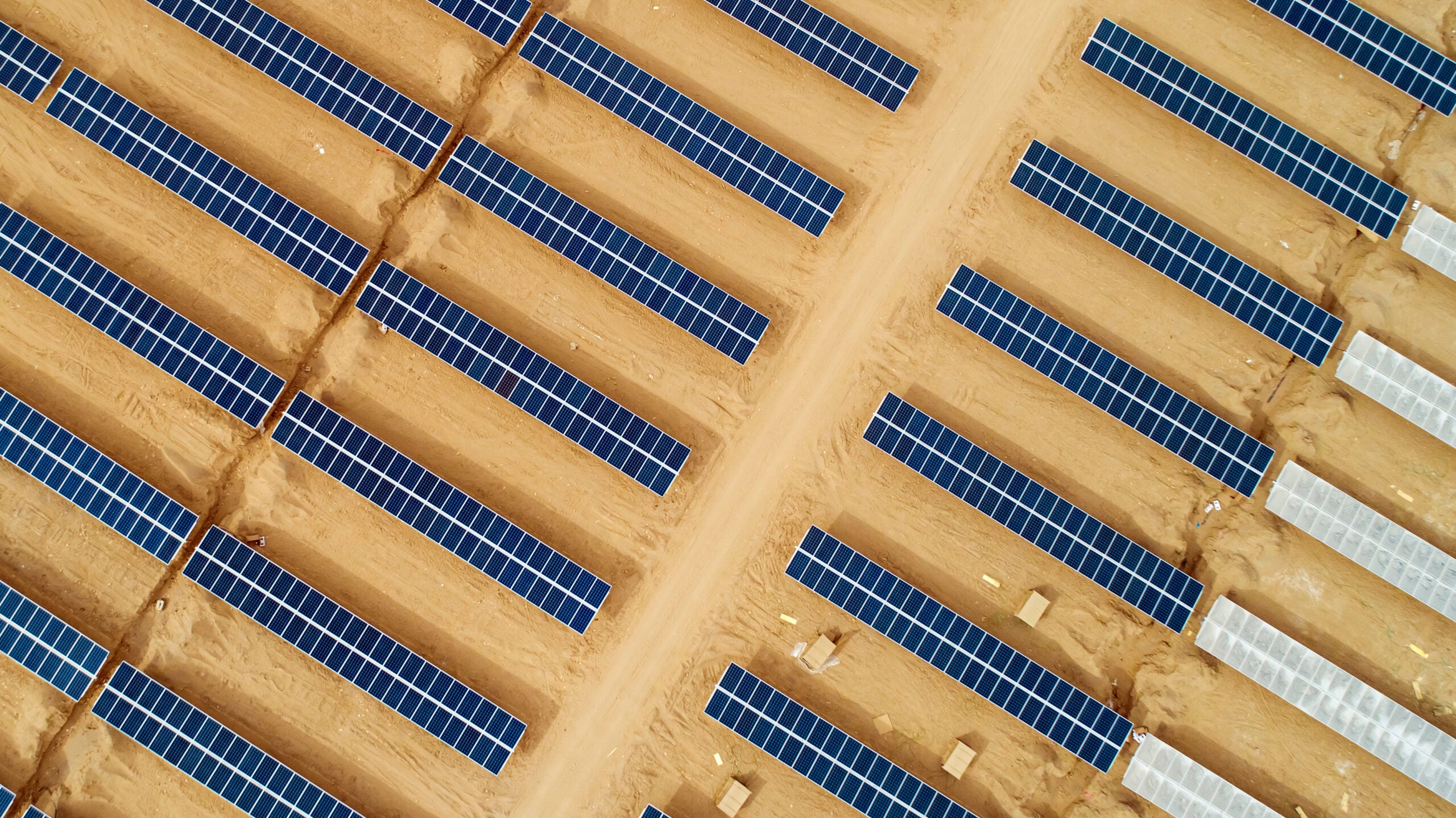

Solar power, along with onshore and offshore wind, is one of the most mature and promising renewable energy sources available. And because solar photovoltaic (PV) panels work well in small off-grid applications as well as medium-sized and larger projects, it is also particularly well-suited to the decarbonisation efforts of developing countries, many of which have access to ample reliable solar resources.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataBut as with any green energy source, access to finance for new projects is essential to push solar adoption to new heights, as recognised in a recent report published in January by trade association SolarPower Europe.

“There will always be some households and businesses with enough spare cash to be able to self-fund solar PV projects,” the report noted. “But finance is what will allow solar to be accessible to a maximum number of power consumers and application segments if sufficiently attractive business models and projects can be put forward.”

With green finance a recurring talking point as the developed world discusses its roadmap to mobilising $100bn a year for climate action in developing countries, how does this discussion impact solar power’s global prospects?

Public finance: international efforts

Public finance is often cited as the essential instigator for vital but high-risk projects to help combat climate change, creating a climate that allows private sector investment to take the baton and run with it.

“Public resources can bridge viability gaps and cover risks that private actors are unable or unwilling to bear, while the private sector can bring the financial flows and innovation required to sustain progress,” wrote World Bank private sector consultant Rachel Stern in a January blog.

In this sense, the wheels of public green finance are finally starting to turn in earnest, with public climate finance flowing into developing countries set to rise from an average of $41bn in 2013-2014 to $67bn in 2020, a 60% increase.

“According to the analysis, modest assumptions about increased leverage ratios would lead to projected overall finance levels in 2020 above $100bn,” reads the UNFCCC’s ‘Roadmap to $100bn’ document. “We are confident we will meet the $100bn goal from a variety of sources.”

Much of this increase is being driven by increased finance flowing from the state level to developing countries, as well as from multilateral development banks (MDBs) and specialised climate funds. The World Bank, for example, announced in May 2016 that it would be allocating a $625m loan to the State Bank of India, along with $125m in concessional co-financing and a $5m grant from the Climate Investment Fund, to invest in widespread solar rooftop installations across the country.

Major international collaborations, meanwhile, are also focusing on freeing up more capital for solar and other renewable sectors. The India-led International Solar Alliance (ISA), which aims to bring together a host of sun-rich nations in the tropics to promote solar power, is looking to mobilise $1tn worth of investments by 2030, through what it calls “innovative policies, projects, programmes, capacity-building measures and financial instruments”, with the international group acknowledging that “the reduced cost of finance would enable us to undertake more ambitious solar energy programmes”.

COP22 in November saw 20 countries sign an ISA framework agreement, with the agreement set to become operational once 15 countries have ratified it.

Blended financing and co-investment: de-risking solar projects for private investors

A potent and relatively recent method of international collaboration is through co-investments and blended financing models, which essentially create microcosms of the traditional relationship between public and private financing for climate projects – public finance to assume the lion’s share of risk, and private investment to fill the gap and sustain development.

Blended and co-financing models involve strong participation or co-investment from MDBs and state-run development funds to help de-risk renewable projects and stimulate private investment. The Global Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Fund, for example, provides layered risk through €112m investment from Norway, Germany and the EU, which it used to entice €110m in further private sector investment for developments, such as solar power projects in India, which traditionally have proven too risky for private investors.

In a recent white paper titled ‘Financing the Green Transition’, Danish institutional investor PensionDanmark elaborated on the renewable energy projects in which it has been able to invest thanks to the stewardship of the Danish Climate Investment Fund, through which PensionDanmark has invested in projects such as solar-powered drinking water production in the Maldives.

“As pure private investments [these projects] would be unfeasible,” wrote PensionDanmark communication consultant Tage Otkjær. “Blended finance can foster private financing for environmentally-friendly projects enabling the diffusion of climate-friendly technology throughout the economy, and at the same time initiate projects, that under normal circumstance would involve a great degree of risk for private investors, [making them] bankable and financially sustainable.”

China leads the way

Of course, it would be impossible to have a serious discussion about green financing without mentioning China, the dominant force in renewable energy technology – five of the world’s six largest solar module manufacturers are now based in the country – and global leader in renewable energy investment. China’s top-down public investment in renewable technologies has spurred massive growth in its domestic industry, with solar playing a prominent role.

The country’s massive investments – it spent $102bn on domestic renewable energy in 2015, more than twice that of the US – have spurred an active private investment scene in solar power. Chinese domestic solar installations doubled to 50GW in the two years up to the end of 2015, and Bloomberg New Energy Finance has estimated that this figure will more than double again with 109GW installed by the end of 2018. The government has stated that it wants to invest a total of at least $360bn in renewable energy sources by the end of 2020.

Minsheng New Energy Investment, the clean energy division of China’s largest private investment corporation, is currently building the massive, privately financed 2GW Ningxia solar project in the north-west of the country which, when completed, will have a generating capacity than nearly matches the solar installed capacity for the whole of Canada at the end of 2015.

“Currently, our financing costs can be on par with those of state-owned companies,” Minsheng New Energy’s executive vice-president Wang Jian told Bloomberg in September.

Given that China hosts just under a fifth of the world’s total population, it could make a massive impact on worldwide efforts to fight climate change just by focusing on its internal market. But the country has also been rapidly ramping up its foreign investments in renewables; the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis tracked 13 Chinese overseas renewable investments of over $1bn in 2016, a 60% year-on-year increase.

The surge of green bonds

Green bonds, which are issued specifically to finance clean energy or other climate-beneficial projects, are another growing mechanism helping to spur investment in solar power and other renewables. Green bonds were first issued in 2007 by MDBs such as the European Investment Bank and the World Bank, but have rapidly increased their presence, with issuances growing from $2.6bn in 2012 to $41.8bn in 2015.

Green bonds allow renewable energy issuers access to a more diverse pool of institutional investors than they are traditionally able, unlocking low-cost capital for infrastructure projects. Investors, meanwhile, get more transparency on where their money will be invested while also having a positive impact on their corporate social responsibility goals.

Understandably, these clean energy bonds have attracted some accusations of ‘greenwashing’ – a PR-inspired ‘clean’ investment that turns out to be more for show than for actually making an environmental difference. But the credibility of green bonds seems to be improving quickly. On the eve of COP22, the Moroccan Agency for Solar Energy (Masen) issued Morocco’s first green bond, worth $118m, to help fund three solar projects with a total capacity of 170MW as part of the country’s massive Noor-Ouarzazate concentrated solar power complex.

Perhaps the best sign of the growing health of the green bond market is the launch in September of Luxembourg Stock Exchange’s Green Exchange (LGX), the world’s first stock exchange-backed platform exclusively for the issuers of green bonds and financial instruments that should also help to address greenwashing concerns.

“We think the time is right,” Luxembourg Stock Exchange CEO Robert Scharfe told Forbes. “New issuance of green securities has taken off since COP21. When we look at the market it is good news that it is growing so fast, but is it growing fast enough? No, it is not…A dedicated green exchange will raise the bar for disclosure. Because we are raising the bar we are making the market more interesting for issuers because we give them more visibility in dedicated infrastructure.”

Available finance capacity for solar and other renewables must grow more quickly if the climate threat is to be tackled, but there are a host of financing models, from development funding to blended financing and green bonds, that are gradually spinning up to meet the challenge. With a new US administration leaning towards climate change scepticism and developed countries such as the UK and Australia pumping the brakes on clean energy investment, if there’s a global green finance leader whose example other countries can hope to follow, all eyes are now rapidly swivelling towards China.