AES has built the 223MW power station named Changuinola I, where project Changuinola 75 was developed. The project, which was initially considered for 158MW installed capacity, was modified to increase the capacity to 223MW on 16 December 2006. The cost of the project increased from $320m to $563m.

Changuinola 75 hydroelectric facility is located in the Changuinola river basin, about 220 miles northwest of Panama City in the province of Bocas del Toro. It lies within the limits of a protected forest named Bosque Protector Palo Seco (BPPS).

Changuinola 75 began generating power in September 2011 with a concession period of 50 years, which may be renewed for an additional 50 years.

The project includes a ten-year power purchase agreement with Panama’s largest utility, Union Fenosa SA. AES began the engineering and geo-technical work and construction in 2007, despite some environmental objections.

Changuinola 75 Project finance

The project has been partly financed (65% of the cost) by entering into a credit agreement with a syndicate of Panamanian banks. In addition, Milbank and a consortium of Central American lenders have financed the project.

Development and construction

The project is owned by AES Changuinola, a subsidiary of the US-based AES Corporation. Civil works will be undertaken by Changuinola Civil Works, a consortium comprising two Danish firms E. Phil & Son and MT Hojgaard, in a joint venture with Alstom Hydro of Brazil.

An engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contract worth DKK1.5bn was awarded to E.Phil & Son while the contract for construction of roads and tunnels was awarded to Alstom Hydro for DKK2.1bn. Sweden-based Vattenfall Power Consultants was awarded a contract worth $8.6m for supply of pipes for tunneling.

The construction equipment was supplied by Volvo Construction Equipment, through its local dealer Commercial de Motores. The fleet consists of 16 A35D articulated haulers, 11 wheel loaders, two Rototilt-fitted EW 180C wheeled excavators and one 70t EC700, a G710B motor grader and a BL60 backhoe loader.

BASF UGC Central America has supplied two spraying manipulators for the tunnel excavation in 2008. The pipes for water and air during construction have been supplied by Alvenius Industrier.

High Panamanian energy costs

Panama is experiencing high energy costs and demand growth. The country has few hydrocarbon reserves (with no natural gas), and imports above 70% of its energy. The new plant integrates the Province of Bocas del Toro into the Panamanian grid, and will also reduce the traditional dependence on imported oil).

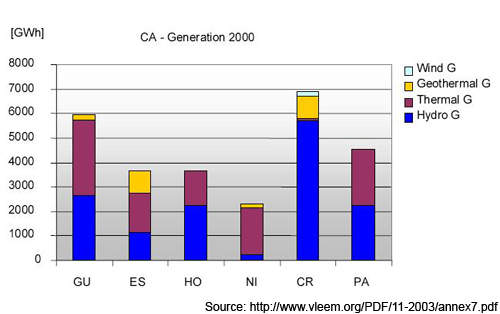

Hydroelectric makes up 75% of Panama’s total energy production. Around 900MW of hydro potential in the country is thought to be economically viable for development by 2015. Panama is expected to invest around $1bn in electricity generation over the next ten years. Nearly 90 hydroelectric projects are proposed, although some are not expected to be built. A 1,100-mile transmission line will connect Panama to southern Mexico.

Changuinola I plant details

The project aims to increase the country’s installed capacity by 15% and energy production by 18%. The current installed capacity of the country is 1,534MW and the annual production is 6,000GWh.

The plant was developed on Changuinola and Calubre rivers. An RCC dam of 99.2m height and 600m length was built in river Changuinola. A reservoir with storage capacity of 130 million cubic metres was formed on 1,394ha of the protected forests of BBPS.

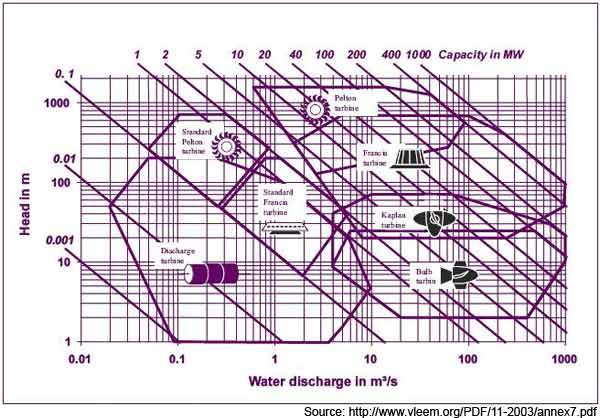

A concrete pressure tunnel of 4,200m in length will carry 221m³ of water per second to the power house. The power house is equipped with two 106.4MW Francis turbines, two generators and two breathing tubes with the floodgates letting the water spill at 11,040m³ a second.

The water from the dam will flow at a 13.4m³ per second and passes through a mini hydro power plant constructed to produce additional power of 9.66MW. A 200m long unloading channel from the power house will carry the water back to river Changuinola.

Transmission and distribution

The output power from Changuinola 75 will be transmitted through a 230KW transmission line from substation to ETESA (Empresa de Transmision Electra). Once the project becomes operational, it will supply 1,040GWh annually to industrial and residential areas in Panama.

The project has a power density of 16W/m², which is more than the acceptable norms (4W/m2) of a Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) project.

Hydropower as long-term replacement for gas/nuclear

The EU-funded Vleem-2 (Very Long Term Energy-Environment Model) project has made an exhaustive global study of hydroelectric power. It suggests that beyond 2020, due to depletion of cheap and near-demand gas reserves, political reasons (public concern over conventional nuclear power), and environmental reasons (global warming), new technologies and increased renewable energy must be put in place.

This will require massive investment in energy infrastructure. In OECD countries most of the growth of renewable energy is expected to come from wind and biomass. Developing countries should see hydropower becoming the fastest-growing renewable energy source.

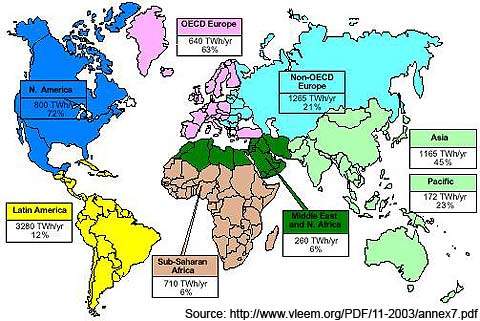

About 19% of the global electricity generation now comes from hydropower, at 2,600TWh. This is about 32% of the economically feasible hydro potential and 18.2% of the technically feasible potential. This means, the current world electricity demand could theoretically be covered by hydropower.

There is much untouched hydropower potential in South and Central Asia, Latin America and Africa, but also in Canada, Turkey and Russia. In the US, modernisation of hydropower stations could add considerable generating power.

Hydroelectric projects need long-term loans with extensive grace periods. That is because they are capital intensive, have a long construction phase with significant risks, with a long useful life. Average hydropower construction costs are between $1,100 and 1,800/kW. Generation costs, particularly for older hydropower plants, are very low. Average generation costs are below a third of those of coal, oil, gas or nuclear.

Environmental concerns expressed

Hydroelectric power stations– especially large ones – can, however, bring problems. They can force people out of their homes (over a million for the Three Gorges Dam in China), decrease wildlife by flooding, block fish from moving up the river to spawning grounds and emit methane.

Plants therefore need careful siting and design, and thorough environmental impact assessments. Environmental groups have accused Panama of ignoring Changuinola’s environmental impacts.

The conservation director of the Center for Biological Diversity in San Francisco wrote an open letter to AES regarding the construction of three dams close to the Panamanian portion of PILA (Parque Internacional la Amistad).

He remarked that they were threatening the biodiverse World Heritage site, and the indigenous Naso and Ngobe groups.

The Center with more than 30 other groups filed a petition to the World Heritage Committee to list PILA as a World Heritage site ‘in danger’ in April 2007. The Committee reviewed and agreed with the threats assessment and requested a joint invitation from Panama and Costa Rica for a World Heritage Centre and World Conservation Union (IUCN) mission to investigate the threats. The Committee regretted that Panama did not report the projects to the World Heritage Centre as required under the World Heritage Convention.