The rise of right-wing governments from 2024’s spate of elections has spotlighted ‘climate populism’ – a movement founded on an anti-elite and traditionalist view of climate change, the energy transition and renewable energy as intrusions into national and economic liberty.

Wind in particular has been villainised. Criticisms levied against wind power range from aesthetic complaints to claims of threats to animal and human life, providing ammunition for reactionary political campaigns.

This narrative is currently being steered by US President Donald Trump, who has returned for his second term in office and is now enacting his long history of opposing wind power.

The anti-wind movement has also gained ground internationally. Notably, Germany’s far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party has ridden a successful populist wave, culminating in a pledge to dismantle wind farms and turbines if it wins the upcoming federal election.

Power Technology delves into why anti-wind rhetoric is being weaponised by populist parties and the implications of this movement for the wind industry.

Populism and the winds of change

Debates over the long-term effects of climate change can appear abstract and intangible to the general populace. Within this, renewable energy sources present visible markers of change that political movements can use to support their agendas.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataBut why has wind power been singled out?

“Wind impacts upon people’s visualisation of the environment and is therefore easy to (literally) view negatively,” explains energy policy consultant Antony Froggatt.

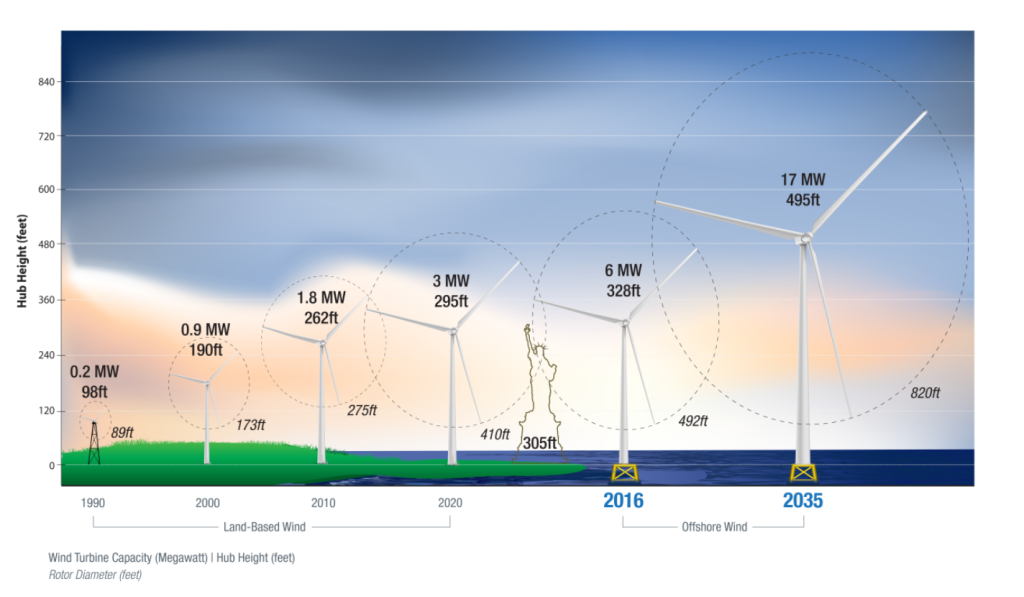

Indeed, wind turbines have grown exponentially in size since the early 2000s. According to the US Department of Energy, onshore turbines have reached around 100m – which is only half the height of offshore turbines – while rotor diameters have grown to an average of more than 133.8m. These measurements are expected to increase even more over the next decade to capture more wind and generate more electricity.

This visibility – and in the case of onshore wind, proximity – has enabled populist parties to successfully promote anti-wind rhetoric to local communities in particular.

Speaking to Power Technology, Dr Patrick Schröder, senior research fellow at Chatham House, confirms that “psychologically, local communities feel threatened by the height of wind turbines.

“But communities have also been instrumentalised by other interests such as climate change denial, which further fuels their opposition against wind energy.”

Momentum has been building for anti-wind narratives since the beginning of the 21st century, but Trump’s landslide victory in the 2024 US presidential election has restoked the fire.

Trump’s objections against ‘windmills’

World Wind Energy Association secretary-general Stefan Gsänger tells Power Technology that “with Trump, we are at a turning point because the fight against renewables has reached a new stage”.

One of President Trump’s first executive orders upon re-entering office was to temporarily suspend new federal leases for offshore and onshore wind projects, pending an environmental and economic review.

The Biden-Harris administration’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) spearheaded the domestic production of wind energy, while the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) allocated $30m for wind project research. Trump has now frozen this support.

“We are not going to do the wind thing. Big, ugly windmills. They ruin your neighbourhood. They are the most expensive form of energy that you can have, by far. And they kill your birds and ruin your beautiful landscapes,” Trump said.

The President’s hostility towards wind power can be traced back to 2011, when he filed a complaint with the Scottish Government to relocate or cancel a “really ugly” offshore wind farm in Aberdeen, near land he had purchased for a golf course. The farm was completed in 2018 after Trump’s legal challenge was rejected in 2015 by the UK’s Supreme Court.

Since then, Trump’s accusations against wind power have ranged from destroying property to causing cancer and disrupting electricity supply.

“He is hijacking the narrative of environmental protection,” asserts Schröder. “As with arguments about health impacts, these are not science-based, and the permitting process considers any such issues.”

Schröder points out another motivating factor for Trump to fight against wind power is his desire to “drill, baby, drill”.

“Where you have wind farms, you can’t go drilling for oil and gas. So, by blocking wind power development, you keep these areas for exploration.”

According to US think-tank the Atlantic Council, Trump’s undoing of clean energy progress will “likely stall US progress in developing domestic clean energy supply chains and manufacturing capacity”.

Indeed, Trump’s actions have already led to broader consequences for wind power across the Atlantic, affecting international investment and circulating disinformation.

Anti-wind blows over to Europe and beyond

Shares in European wind companies have been dropping since Trump’s election victory in November, and this has worsened with the President’s suspension of wind permits.

On the first day of Trump’s presidency, shares in Danish wind giant Orsted dropped by 17%, while those in its counterpart Vestas fell by nearly 3%. Meanwhile, Italian energy solutions provider Prysmian announced its abandonment of a planned plant in the US to make cables for offshore wind parks.

Froggatt explains that Trump making the US less attractive for wind investment may mean more investment for Europe.

Despite this, anti-wind rhetoric is growing ever-louder in the continent as well, led by Germany’s far-right populist AfD party.

Currently polling second for the upcoming federal election, the AfD has been vocal in condemning wind power, using the same arguments as Trump. Party leader Alice Weidel recently pledged to tear down “windmills of shame”, striking a chord with rural communities.

This has been echoed by Christian Democrat leader Friedrich Merz, who has called wind turbines “ugly because they do not fit into the landscape”, adding that they are a “bridging technology” to eventually be dismantled.

Pre-election, the success of such messaging remains to be seen.

However, Germany is currently experiencing its most prolonged period of below-average wind power generation since early 2021, attributed to a sustained period of low wind speeds, which could give credence to anti-wind claims.

As such narratives gain political prominence, Gsänger emphasises that “anti-wind campaigns are orchestrated by small but well-organised networks”. He cites a recent investigation that traced 440,000 objections to 40 planned wind projects in southern Germany to only 6,660 people, an average of 65 objections submitted per person.

“Not all opposition is baseless,” says Schröder, noting cases in which wind turbines encroach on indigenous lands and threaten environmental conservation. Fishing cooperatives across the world have also objected to offshore wind installations as their effects on marine ecosystems continue to be debated.

“But in many cases, there are bigger political interests, like trying to stop the energy transition,” states Schröder.

In Australia, there has also been a rise in protests propagating the same claims against wind power of unreliability, high prices and land usage. This culminated last year in the ‘Reckless Renewables Rally’ outside Parliament House in Canberra where protestors and politicians gathered to oppose the federal government’s 2030 renewables target.

“There are anti-wind groups everywhere,” confirms Gsänger. “The battle between fossil fuels and renewables has become worse than expected.”

The prospects for anti-wind

While the anti-wind movement has hit wind energy policy and industry shares, the technology remains steadfast for its relative affordability and scalability – strengths that are crucial for renewable energy security.

For instance, Trump’s anti-wind rhetoric has been incongruous on the national and state-level, as wind has become a key part of the US’ energy mix.

In 2023, 10% of total US utility-scale electricity generation was from wind, driven by support from the IRA and BIL. The 11 approvals granted for commercial-scale offshore projects in the past four years amount to 19GW.

It is also notable that four of the five US states with the highest wind capacity today – Texas, Iowa, Oklahoma and Kansas – are Republican-led.

With a cumulative installed capacity of 151GW, Power Technology’s parent company, GlobalData, forecasts that the US wind power market will continue to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of more than 6% by 2035.

The market is also forecast to reach a value of $34bn by 2030, which Manès Weisskircher, head researcher at TU Dresden University, identifies as an obstacle to anti-wind crusaders. “Direct economic benefits for local communities close to wind parks increase local acceptance,” he says.

Gsänger concurs. “There are concrete economic benefits to wind power, including for Republican states. People directly feel, in their pockets, that wind power is good for them and renewables have extreme market success.

“I am confident that even Trump will not be able to remove everything.”

Similarly, it would be challenging to extract wind from Germany’s energy mix, as it meets at least 20% of the country’s electricity demand. In 2024, the European nation achieved a record year with 9.2GW of onshore approvals.

However, differentiating valid opposition to wind power from the weaponisation of environmental and sociological complaints is becoming increasingly complex, especially due to the relationship between anti-wind movements and the fossil fuel industry.

Research from Brown University mapped relationships between fossil fuel companies, climate denial think tanks and anti-offshore wind community groups in the US, finding that they often share “legal support, public speakers, leadership, funding and tactical subsidies”.

Gsänger recognises the forcefulness of the fossil fuel industry in keeping this movement alive. “It is one of the biggest sectors worldwide, and they have a lot to lose. These networks are effective.”

He believes that amid the controversy, distributed wind power may be an “ideal solution” to keep the benefits of the technology in people’s hands.

The consensus among experts is that we will have to “wait and see” how populism’s anti-wind movement plays out.

“For wind developers, it will be difficult to plan without the continuous expansion we have seen in the past,” says Schröder. “Much will depend on which government is in power, whether new permits are given and if any incentives are provided for profitable operations.

“But polarised politics and populism will continue to have a real impact.”

Global wind power development remains on an upward trajectory for now, with an expected installed capacity of 3.2TW by 2035, according to GlobalData. The technology’s cost-effectiveness and rapid deployment capabilities will continue to present strong counterarguments against anti-wind rhetoric.

“The overall trend in many countries remains toward the expansion of renewables, albeit often slower than climate action advocates would hope for,” summarises Weisskircher. “Considering the significant transformation under way, it is not entirely surprising that energy infrastructure projects face critical voices. Large-scale change always involves challenges.”