If you build it, the innovators will come. Solar has become a metaphor for how investment can attract development to an expensive renewable technology. Research and development then causes prices to fall and the virtuous cycle can quickly cause prices to crash.

This variation on Moore’s Law holds true in solar development: Since 2000, the price per kilowatt-hour has fallen exponentially. Some measurements show an 89% decrease over ten years. Even since 2016, the median cost of solar installations larger than 10MW in the UK has fallen by 25%.

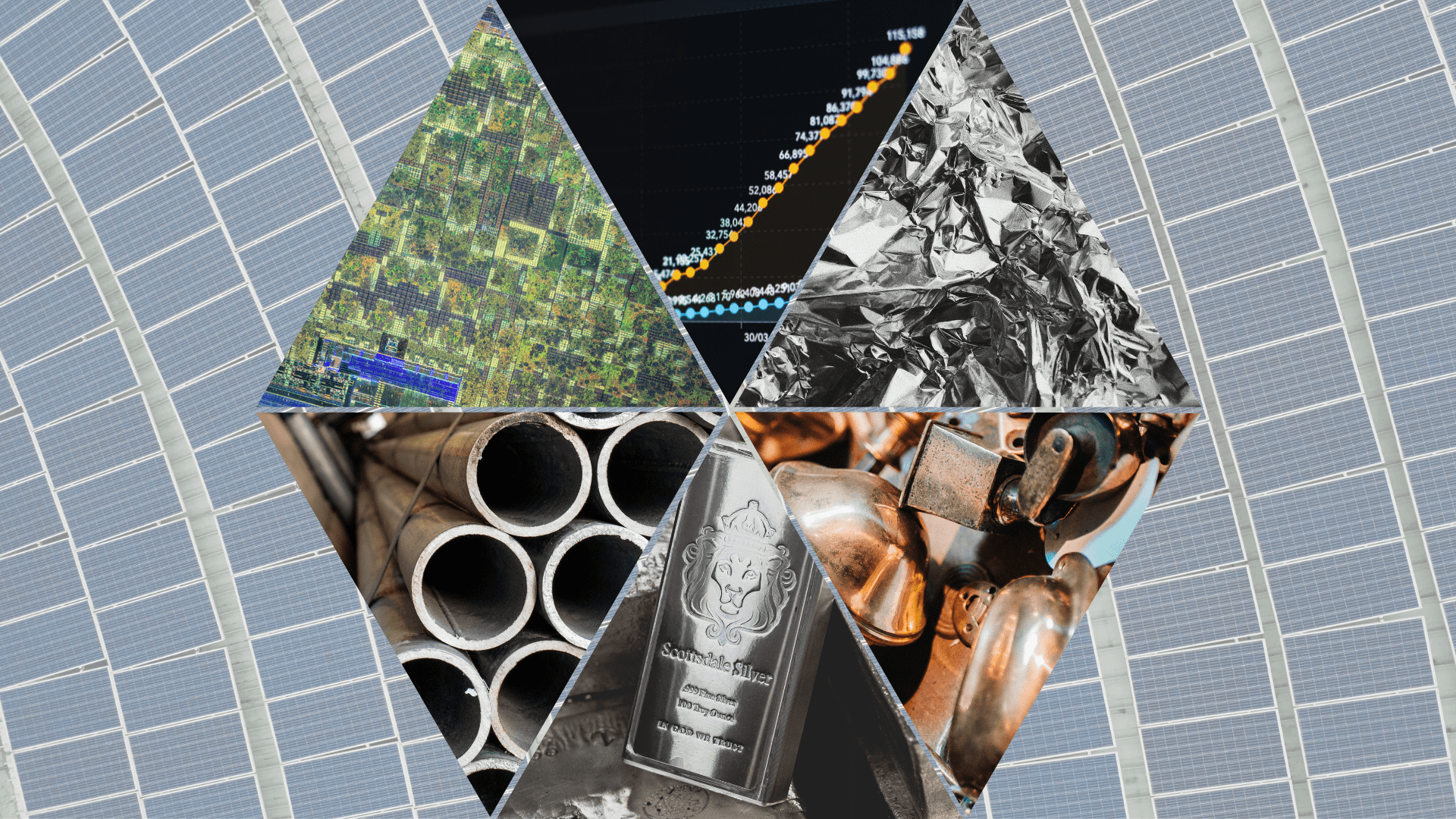

Solar is often the cheapest power source, and analysts expect its price to keep falling. DNV’s recent Energy Transition Outlook expects costs to halve again by 2050. But now the dramatic fall in price has started to slow, with several core materials rising in price.

In the last year, some modules have become 25% more expensive, with raw material prices pushing up the cost of the energy transition. An analysis by Rystad Energy suggests that the prices could threaten 50GW of solar developments planned for 2022;’ 56% of total planned development. Analysts also point to the 500% rise in shipping costs as a contributing factor.

Supply chains have only just started showing the effects of Covid-19 disruption, which takes some of the blame. However, some prices have trended upward for years, and could prevent the decline in solar costs as they move ever higher.

Price of silver wobbles upward with solar metal demand

Almost all solar panels rely on silver components, despite engineers’ efforts to minimise use of the precious metal. Silver’s high electrical conductivity makes it a great material for electrodes, and silicon wafers coated in silver powder often form the basis of conventional photovoltaic cells.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataHowever, these come at a cost. In 2020, when solar investment slumped because of the pandemic, PV solar installations still used 3,100t of silver. This marked a 2% increase on the year before, and approximately 10% of total global silver supply in 2020. After years of rising slowly, the Silver Institute expects PV silver demand to rise to its highest ever level this year.

At the same time, newer solar models attempt to minimise silver use to make manufacturing costs more reliable. In recent years, silver’s price has varied massively. Last year, prices flew between $12 per ounce and $30 per ounce within six months as Covid-19 worsened price instability. More broadly, silver prices have gradually moved upwards, pushing manufacturing costs up with them. From post-millennium lows of less than $5 per ounce, silver has rarely dipped below $15 since 2007.

Solar drives the polysilicon market, and has most exposure to its price

As mentioned, the overwhelming majority of solar panels rely on polycrystalline silicon, known as polysilicon. The material is a type of semiconductor, and is abundant in the earth’s crust, so price is decided only by processing capacity. This has massively grown in the last three decades, mostly to accommodate the tremendous expansion of the solar industry.

Other semiconductor innovations have also demanded more polysilicon over time, but in nowhere near as much as solar. Between 1995 and 2014, demand for silicon in solar cells increased by more than 160 times. Solar has become the main consumer of polysilicon, driving 90% of demand from materials suppliers. Polysilicon manufacturing has grown to accommodate this, but in doing so suppliers have resorted to unethical measures.

In 2020, China produced 77% of the world’s polysilicon. Specifically, much of this comes from the Xinjiang region, where the country engages in slavery and other human rights abuses as part of an ethnic purge of local Uyghur Muslims.

In response, solar industry bodies have committed to cleaning up the supply chain. The US enacted trade sanctions against companies involved in human rights abuses, causing importers to source more expensive materials elsewhere. Both of these measures have taken effect relatively recently, and work must still be done to remove slavery from supply chains.

Supply chain reforms have contributed to a global supply shortage, but again, the main cause comes from Covid-19. Disruption to semiconductor manufacturing lines has caused a ‘bullwhip effect’ of greater disruption further down the supply chain. Since mid-2020, polysilicon prices have more than tripled. From September, most of China has experienced blackouts because of power shortages, which has not helped the situation.

Aluminium feels the bite of power shortages

Aluminium has a high conductivity, allowing it to replace silver in some applications. This has led some solar producers to replace silver components with twice the quantity of aluminium while still making savings with the cheaper metal.

However, while aluminium remains comparatively cheap, its cost has risen rapidly since the onset of the pandemic in April 2020. From a low of $1,460 per tonne, prices have doubled to more than $3,000 per tonne. The current 13-year high stands well above pre-pandemic prices, which remained around $2,000 per tonne since 2016.

Disruption from Covid-19 has had a direct impact on prices, but also caused several indirect issues in the supply chain.

Aluminium refining requires huge amounts of power, at the same time as many heavily industrialised countries face power shortages. This power consumption makes aluminium very emissions-intensive, giving reason for worry in an era of green taxes. The movement to reduce global carbon emissions has also rapidly increased demand for aluminium in solar and wind generation.

Magnesium shortage raises steel price while semiconductors push the other way

The basic framework of many solar panels relies on steel, both for its rigidity and its price. As an industry, steel has struggled with the growth of cheap Chinese product. This has moved a lot of production to China, making the market fragile during the pandemic.

Steel comes in many forms, but some have more than tripled since the worldwide onset of Covid-19. Market experts have said they expect prices to keep rising into 2022, with consequences for steel costs. In the US, massive buyouts have consolidated the market into a duopoly, worsening competition and prices. In India, local steel prices have risen by more than 50%, while British Steel has increased prices by more than 40%.

Steel production relies on a steady supply of magnesium, 87% of which comes from factories in China. Industrial disruption there has pushed steel producers across the world to the edge of shutting down production. This has already had an effect on prices, but the greatest effect will come later.

Ironically, the semiconductor shortage has actually helped steel prices by keeping car production down. Once semiconductor production ramps up, car production will too, consuming more steel and causing new price rises.

“Plugging the copper gap will require an investment of $325bn”

Electricians have used copper cables since the discovery of electricity because of the metal’s great conductivity. In industrial applications, copper remains the material of choice for transformers, inverters, and some high-voltage cables.

This has made it a key material in solar farm construction. An efficiently-designed solar plant could use approximately four tonnes of copper per MW of peak capacity. The energy transition as a whole has become the primary global user of copper, with approximately 60% of supplies going toward electric vehicles, transmissions infrastructure, wind, and solar power.

Copper’s range of uses make it a valuable material, but prospectors have found few new deposits to replace depleting mines. Investment bank Citigroup estimates that copper demand will exceed production by 521,000 tons this year. This deficit will continue to grow as the energy transition accelerates, pushing the solar price up.

Julian Kettle, vice chair of metals at analysts WoodMackenzie, believes that: “without additional substantial investment, production will decline from 2024 onwards. Coupled with demand growth, this decline in output will lead to a theoretical shortfall of around 16 million tonnes by 2040. Plugging that gap requires an investment in the region of an additional $325bn.”

This production deficit and speculation over renewables’ increasing demand for copper has driven price rises this year. While copper prices have risen and fallen since the millennium, in 2021 they have risen much faster than before.

Economic analysts believe this may mark the start of a long-term copper price rise. This would only reverse when most of the construction and development of the clean energy transition finishes.