The 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan dealt a significant blow to the public’s trust in nuclear power, not just in Japan, but globally.

The 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan dealt a significant blow to the public’s trust in nuclear power, not just in Japan, but globally.

Six years on from the accident, some large nuclear power users, including Japan and Germany, have dramatically rolled back capacity. Japan, which once had 50 nuclear reactors in operation, now has only three, while Germany went from 17 to eight.

The industry also faces other challenges, such as increasing cost competitiveness from renewables and cheap natural gas, especially in the US, which has an abundant supply from domestic shale reserves.

Yet, as the Lloyd’s Register report states, nuclear power’s low-carbon credentials ensure it will be integral to lowering global carbon emissions.

New capacity is still being built despite cost pressures and public wariness. In the UK, Hinkley C has been approved and the first small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs) could be operational by 2030. Three new reactors are scheduled to come online in Japan and the US currently has four under construction– so is public opposition still a notable problem for the sector?

Heidi Vella discussed the trials of the nuclear sector’s development with energy experts: World Nuclear Association communications manager David Hess, UK-based National Nuclear Laboratory director of external relations Adrian Bull, US-based Union of Concerned Scientists senior scientist Edwin Lyman, and UK-based law firm DWF head of nuclear and joint head of environment Simon Stuttaford.

Heidi Vella (HV): Are consumer attitudes to nuclear prohibitive?

World Nuclear Association, David Hess (DH): It’s hard to say with certainty what the public attitudes towards nuclear energy are in countries such as Japan, South Korea and Malaysia. Certainly, media surveys started after the Fukushima accident suggest there are ongoing challenges with nuclear energy in Japan, but interestingly, this doesn’t seem to be influencing election outcomes. In the last federal election, the most openly pro-nuclear candidate, Shinzo Abe, won in a landslide and has introduced a policy, without much fanfare, that will see nuclear generating 22% of Japanese electricity in 2030.

National Nuclear Laboratory, Adrian Bull (AB): After Fukushima there was a dip in support but 12 months later it went back up. Most people tend to be concerned about nuclear waste rather than the danger of nuclear reactor operation incidents. There is some concern around the high capital cost of building nuclear stations.

Union of Concerned Scientists, Edwin Lyman (EL): I don’t think public perception plays a big role in the challenges nuclear is facing, certainly not in the United States or in most countries across the world, except Japan or Germany. Even after the Fukushima accident. In the 1980s, there was a significant anti-nuclear movement that was very vocal. Now it is very marginalised to environmental groups or those living near reactors.

DWF, Simon Stuttaford (SS): We have seen a noticeable shift in consumer attitudes to nuclear. Even some staunch opponents are beginning to appreciate the important role nuclear will play if the UK is to meet its ambitious emissions targets. Nuclear is now considered to be a safe industry, with an excellent safety record. However, understandably, the public still has concerns over the cost of new nuclear and the issue of safe and reliable waste storage.

HV: What can the industry do to garner more support from the public?

AB: I think it is important we engage with people, however there is a danger of over communication. We have done quite a lot of work in the industry, looking at how we can engage with the public and in what situation. If I was to go out into the street and start telling people how great nuclear energy was, people would probably walk away more concerned than before because they would wonder why that conversation was happening. It’s like the airplane industry – it doesn’t labour the point about how safe flying is. However, around policy and individual projects, it is important the industry is out there actively making information available so people can make an informed choice.

EL: I think it [the nuclear industry] does itself a disservice by not engaging about what it can and can’t do. It needs to stop worrying about messaging and deal with its own systemic problems and stop blaming regulators for its inability to form a financing mechanism that works.

SS: The nuclear industry must continue to communicate its benefits and promote itself in a more transparent and straightforward manner. It needs to build at least one plant on time and within budget, to prove it is possible and to instil faith in the industry.

HV: Can nuclear power compete against renewables and cheap natural gas, particularly in the US?

AB: The cost of energy from Hinkley C is significantly higher than the current price of electricity, but it is also lower than the price agreed for tariff rates for many renewable projects. I think it reflects a government that wants low carbon and a reliable, 24/7 electricity to the grid. The government has got to make sure the market delivers the right combination of affordable, reliable, safe and low carbon energy and it has had to put some mechanisms in place to do that.

EL: Ten years ago, the nuclear power industry said that once you pay off the plants upfront capital costs they will be cheap to run. That has been challenged lately with the collapse of the US industry and the low price of natural gas. The new nuclear power plants are – by and large – experiencing the same cost and overlays as the plants back in the 1970s and 1980s. The prospect that nuclear could replace 80% of fossil fuel generation worldwide by the 2040s is totally unrealistic.

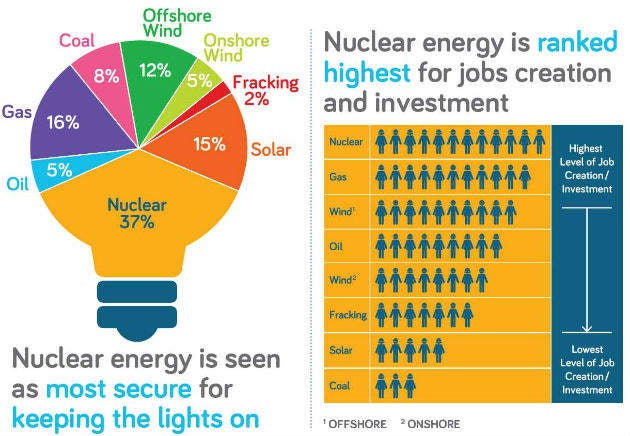

SS: Absolutely. Nuclear satisfies the requirement for new electricity capacity being low-carbon, secure and affordable, as well as having the potential to create jobs via infrastructure projects – a necessity in the post-Brexit world. According to a recent joint report by the International Energy Agency and Nuclear Energy Agency, nuclear generation compares very favourably to other technologies, both baseload and low-carbon, when it comes to affordability.

Of course, there is a role for both renewables and natural gas, but both come with limitations. The intermittent nature of renewables fails to address the need for a reliable baseload source of energy, while natural gas poses a threat to challenging emission targets. This is particularly the case in the absence of carbon capture and storage technology (CCS).

HV: Could SMRs be the key to securing the future of nuclear?

AB: SMRs are a tenth to a fifth of the power output of larger plants and can be located inland, unlike large plants. They are easier to finance because they are less expensive in terms of the overall initial project, but then you might build two or five in a sequence. This limits your financial exposure because you build the first one, then use the revenue from this to fund the second and so-on. It is almost like nuclear Lego.

SS: With the right support, SMRs are potentially a promising solution to bridge the gap before we get to new nuclear. With a capacity of less than 300MW, these shrunken versions of larger plants offer a lower initial capital investment, greater scalability and location flexibility. However, there are some regulatory challenges to be overcome for them to become a reality in the UK in the timeframe they’re needed.

DH: SMRs are a very promising technology which many countries are interested in – all established nuclear countries, except those with phase-out policies, and many newcomers, such as Saudi Arabia and Jordan. Companies in Russia, China, South Korea, France, Argentina, the US, Sweden, the UK, and probably other places besides, are all developing technology. It’s a genuinely exciting field as it opens-up new market niches for nuclear energy, including more flexible siting, more nimble demand response, and direct substitution for old fossil units. We should expect to see the SMR market bloom in about ten years as designs are brought to market. Possibly sooner in Russia and China.

In terms of helping the industry to overcome cost challenges there are reasons to be optimistic, but we need to see some important market and regulatory changes, especially with licensing. Governments need to act decisively if they want to realise the benefits of SMRs. I tend to see SMRs as a complementary technology to large reactors, rather than a competitive one. Industrialising countries with growing energy demand and over ten million people will probably find that large reactors are the more economic option.