A team of researchers from Michigan State University (MSU) has developed a transparent solar concentrator. The concentrator is designed to absorb invisible rays of light and convert them into grid-quality electricity, providing a source of clean power with minimal aesthetic impact on a building or device.

Alongside advancements in the technology, materials scientist Richard Lunt and his team have been evaluating the potential for the solar concentrator in the US. The joint paper titled ‘Emergence of highly transparent photovoltaics for distributed applications’, was published in Nature Research scientific journal in 2017. It highlights the great expanses of glass that could become power sources, and how much untapped energy they represent.

“Highly transparent solar cells represent the wave of the future for new solar applications,” Lunt said in the report. If the technology could be rolled out widely, it could, theoretically, reduce US carbon emissions from power by more than 700 million metric tonnes a year. Appealing to environmentalists and architects alike, see-through solar could enable a shift away from bulky solar panels without a reduction in energy generation.

In an effort to commercialise transparent solar technology Lunt founded the company Ubiquitous Energy, with report co-authors Richa Pandey as principal scientist and Miles Barr as CEO. Under this MIT startup, the technology has been named Clearview Power and is currently in the pilot stage. Ubiquitous Energy is currently preparing prototypes to help make transparent solar a reality as soon as possible.

Tuning in to the right frequencies

Transparent solar technologies have been researched before, but their limited efficiency and tendency to change the colour of the light entering windows made them undesirable. Many efforts over the last 30 years have focused on altering conventional solar panels for use as windows or on glass; however, photovoltaics (PV) use ambient light at the same frequencies the human eye can see, and as such cannot achieve a high enough level of transparency to make them attractive.

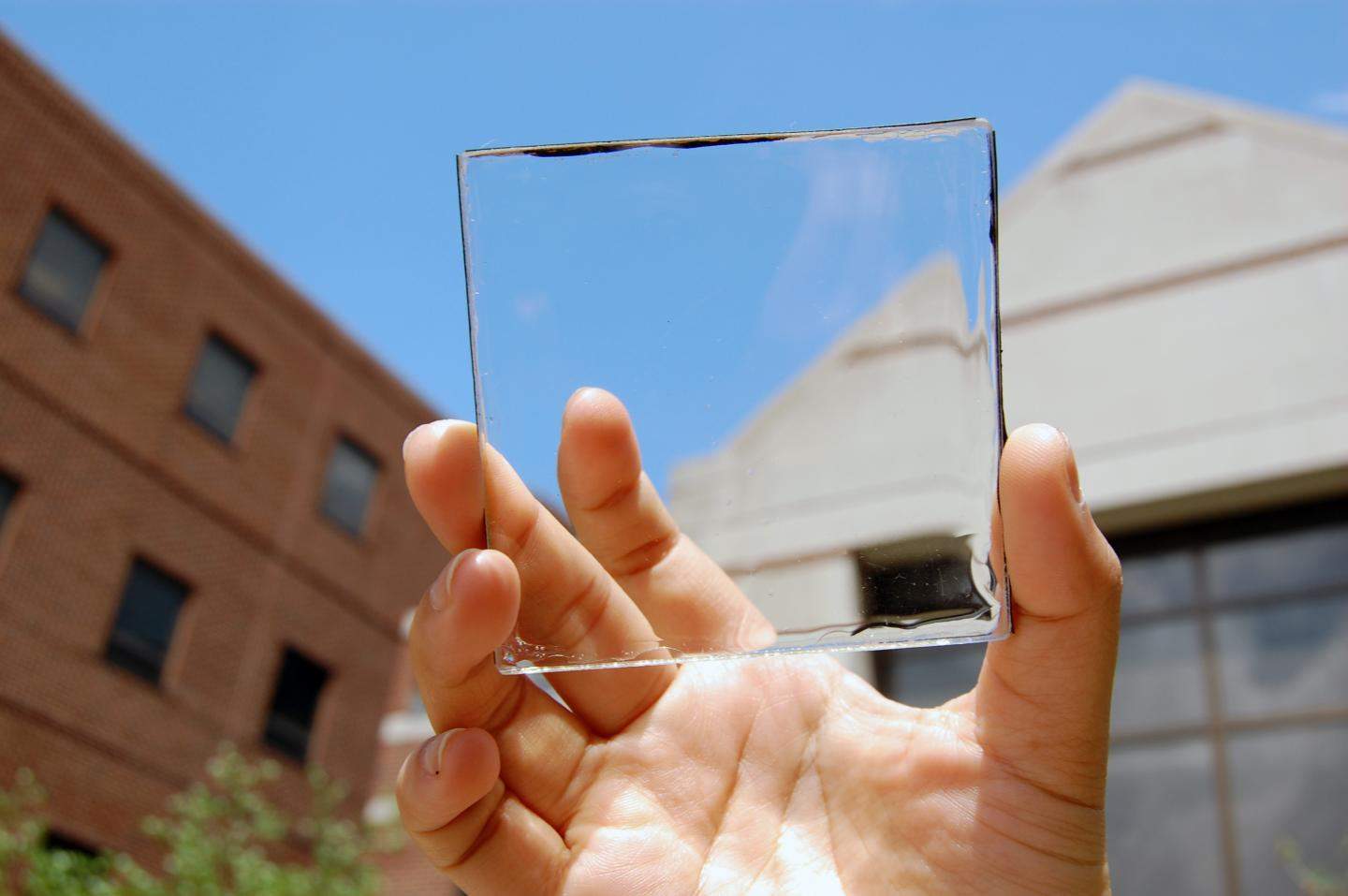

Lunt and his team at MSU have taken a different approach, developing a concentrator instead of a solar panel in the traditional sense. While visually similar to a piece of glass, the concentrator is a thin, flexible layer of organic materials which can be placed on windows, phone screens or any flat, clear surface.

The concentrator can be ‘tuned’ to pick up specific sections of the light spectrum, allowing it to harvest the energy from only ultraviolet and near-infrared wavelengths of light, both of which are invisible to humans.

“Because the materials do not absorb or emit light in the visible spectrum, they look exceptionally transparent to the human eye,” Lunt explained.

This transparency is what makes the concentrators both aesthetically pleasing and versatile, opening up a range of possibilities. It lies on glass at less than 1/1,000th of a millimetre thick, and is virtually indistinguishable from the glass. Beyond covering skyscrapers and other buildings, the technology could be applied to electric vehicles, for example, allowing them to charge as they drive, vastly increasing the distance they can travel and reducing reliance upon the national grid.

“We analysed their potential and show that by harvesting only invisible light, these devices can provide a similar electricity-generation potential as rooftop solar while providing additional functionality to enhance the efficiency of buildings, automobiles and mobile electronics,” said Lunt.

Billions of glass surfaces

The potential solar power presents is huge and uptake has been growing consistently. In 2016, more solar capacity was installed than any other power source, marking an important milestone in the gradual shift from heavily polluting fossil fuels. This was particularly noticeable in the US, where, for the first time, more solar was installed than any other power source, amounting to 39% of new installations. This is predominantly due to the drop in the cost of PV, which has fallen by 70% since 2010.

However, the solar percentage of the overall capacity the US remains comparatively small, at just 49GW. This provides around 1.8% of America’s energy demand and, while 2016 saw the biggest ever increase in solar capacity installation with 4,626MW of new PVs – representing a 95% increase on the previous installation record set in 2015 – this is still a long way from fulfilling solar technology’s potential.

For instance, rooftop solar energy alone has the estimated potential to meet 40% of US power demand and, Lunt says, combined with his transparent technology, “the complimentary deployment of both technologies could get us close to 100% of our demand, if we also improve energy storage”.

Lunt’s team’s research backup these confident claims with estimates that the US has five to seven billion square metres of glass surfaces, which, if used to harvest solar energy, could produce a similar amount of power as rooftop solar. Combining the technologies is ideal, therefore, for taking advantage of all available surfaces and minimising the aesthetic impact of solar power.

Matching the efficiency of PV

Transparent solar technology could have a significant impact upon energy generation, helping ease the transition to zero-carbon power sources. However, the technology will need to become more efficient before it can make a real difference. Currently, it operates at about 5% efficiency, while solar PV is between 15% and 18%.

It’s unlikely that transparent solar will be able to equal the efficiency of opaque panels, and it certainly won’t replace them, but it’s still early days for the technology and Lunt is confident that as it progresses it will become as much as three times more efficient.

“Traditional solar applications have been actively researched for over five decades, yet we have only been working on these highly transparent solar cells for about five years,” Lunt said. “Ultimately, this technology offers a promising route to inexpensive, widespread solar adoption on small and large surfaces that were previously inaccessible.”