NAIROBI – It felt at first like a climate summit born out of chaos. From the confusion around which leaders would be appearing (at one point French President Emmanuel Macron’s name was listed on the official app), to the queues that stretched around the block at the accreditation centre, with tales of people lining up for five hours only to be told that their names could not be found in the system.

Once proceedings kicked off in the Kenyatta International Convention Centre – a striking, brutalist monolith in downtown Nairobi – few events seemed to take place in their scheduled location, or at their scheduled time. A sudden, bumper influx of some 20 African leaders on the second day ensured the entire schedule of talks and panels fell some four hours behind, as leaders gave carbon copy speeches calling for more climate action, more climate finance and more development opportunities for Africa.

But whatever way you spin it, the Africa Climate Summit represents a landmark moment for the continent. The unanimously adopted “Nairobi Declaration” represents the first time African leaders have reached a joint position on the question of climate change and climate policy, and it establishes a new, empowered voice that will be taken forward to future climate summits.

“This declaration will serve as a basis for Africa’s common position in the global climate change process,” reads the cover text of the final document. “No country should ever have to choose between development aspirations and climate action.”

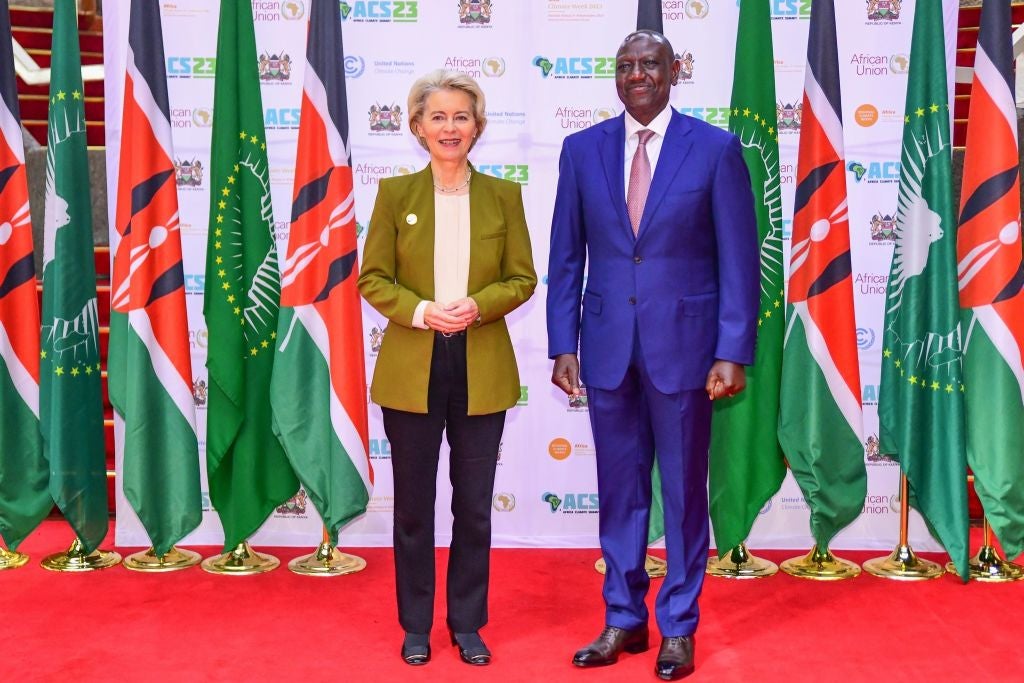

William Ruto, the Kenyan president who was the driving force behind the Africa Climate Summit, can leave the summit confident in the knowledge that it was a diplomatic success.

“The Nairobi Declaration,” said Ruto at the closing plenary, “reaffirms our determination and sets the stage for a new phase in the global climate action and sustainable development agenda, giving the future of socio-economic transformation a distinct and affirmative African character.”

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataAn ambitious declaration supported by all African leaders

The Nairobi Declaration was later officially released at an outdoor press conference, where national anthems played, fireworks were set off and those leaders who had not yet returned home waved to delegates gathered in the intense Nairobi heat.

Ruto – who was elected president in 2022 – stood alongside leaders including Salva Kiir of South Sudan, a country where 76% of the population require humanitarian assistance, says the World Bank; Isaias Afwerki, the despotic president of Eritrea, who leads a country that comes second to last in the Press Freedom Index after North Korea; and Mahamat Déby, leader of Chad, an East African country whose neighbours have been riven by civil war (Sudan) and a coup d’état (Niger) in the past few months.

African nations differ hugely in their cultural character, landscapes and political situations. But with the continent warming faster than the global average (at 0.3°C per decade), no country currently ranked higher than “middle income”, and a 1.3 billion population that is expected to double by 2050, all countries have significant climate change and developmental concerns, which the Nairobi Declaration seeks to address.

Keep up with Energy Monitor: Subscribe to our weekly newsletterIt includes calls for the global financial system to be reformed, noting that the cost of borrowing is significantly higher (around eight times higher than Europe). It also calls for the long-promised pledge for $100bn in climate finance for the developing world to finally be met; for Africa’s renewable generation capacity to increase from 56GW in 2022 to at least 300GW by 2030; and for new industrial opportunities to process raw materials within the continent (unprocessed minerals currently account for 70% of total African exports).

Strong ambition – but “general” in wording

Many commentators in the climate space have reacted positively to the contents of the declaration, and to the conference more generally.

“The Africa Climate Summit has asserted new leadership on global climate action from the continent most vulnerable to its impacts,” says Alex Scott, programme lead for climate diplomacy at the think tank E3G. “Kenya has shepherded a declaration by African leaders with clear calls for accelerated climate action, mobilising a massive scale of investment in green transition and adaptation in Africa, and reforming the finance system for fairer financing and debt management.”

Andrew Herscowitz, executive director for North America at think tank ODI, reacted positively to the bold call for reform of the global financial architecture, saying: “African leaders face a monumental task: addressing climate loss and damage, dealing with a debt crisis, while at the same time financing a green energy transition.

“The World Bank and other public lenders to developing nations could put a huge dent in the problem; but must adjust their approach to investment. This means behaving more like the development institutions they were designed to be than banks maximising financial returns.”

But amidst some glowing reviews from international commentators, the sense on the ground at the Kenyatta Centre was that while the declaration marks a seminal moment, it does not necessarily advance climate policy in a meaningful way.

“It is certainly historic to have a summit that is really looking at Africa, and the continent’s role in both addressing climate change, but also looking at the opportunities that we could be able to leverage within the context of climate change,” Lily Odarno, a director at think tank Clean Air Task Force (CATF), told Energy Monitor.

Read more from this author: Nick Ferris“Given the discussions we were having beforehand, though, nothing really surprised me in the final cover text, and in fact the language was a bit broader and more general than I was originally hoping to see.”

Odarno adds that now the “hard work begins”, as civil society must push African governments to achieve the goals laid out. These goals currently remain just that: goals, with no accountability mechanism established to ensure that governments achieve them.

Climate activists crowded out

Among the activists who have gathered in Nairobi, there is dismay that community voices have not been sufficiently incorporated into the summit, and also at the lack of ambition to wind down fossil fuels. The cover text mirrors language first unveiled at COP26 on fossil fuels – to “phase down coal” and end fossil fuel subsidies – with no mention of oil and gas, which remain key to many African countries’ development plans.

“As Africans grapple with the debilitating impacts of the climate crisis, African leaders have been engaged in rhetoric and false solutions such as fossil gas and carbon markets that seek to delay meaningful climate action and the much-needed just transition away from fossil fuels, that is central to the fight against the climate crisis,” Charity Migwi, a Kenya-based campaigner at 350Africa.org, told Energy Monitor.

“There’s nothing new about the nature of the wording of the declaration: Rather than phase out fossil fuels, the declaration indicates a phase down of coal, which isn’t a new thing and hasn’t been implemented yet,” she adds. “We can’t afford to take baby steps when the scale and speed of change needed should be radical.”

Marina Agortimevor, a Ghana-based coordinator at campaign group the Africa Coal Network, who attended the summit in Nairobi, says that to her mind, there was not enough civil society presence at the summit. For her, this means the summit resulted in an outcome characterised by big policy announcements, rather than the community-led sustainable development projects, which are what is most required in Africa.

“We need a greater presence of communities and indigenous people actually in the meeting rooms at the summit,” she says. “Otherwise we end up with an outcome such as we have now: One that is all about profits for companies, rather than what people need.”

Agortimevor and other climate activists convened a “people’s summit” across the bridge from the Kenyatta Centre, which released its own, far more radical declaration, which includes calls for “trillions in climate reparations”, as well as an outright rejection of fossil fuels and carbon markets.

$23bn in financial pledges “a drop in the bucket”

The other big story at Africa Climate Summit was an array of financial pledges made by visiting leaders and dignitaries, which in the end totalled $23bn.

This included announcements such as a $4.5bn commitment from the UAE to boost renewable energy in Africa; a new $60m partnership to expand grid access in rural Burundi; a $30m pledge from the US to accelerate food security efforts across the continent; and €12m ($12.8m) in grants from the EU to support Kenya’s green hydrogen strategy.

But while some of the numbers are big on paper, experts familiar with the matter are unimpressed.

“While some new financing commitments were made, the small numbers from the likes of the EU, US and UK stood in stark contrast to a $4.5bn pot of renewable energy investment funds organised by the UAE,” says E3G’s Alex Scott.

“The $23bn figure is a drop in the bucket compared to what Africa actually needs”, says CATF’s Odarno. “The Africa Development Bank has estimated that we need $2.7trn in extra finance for the continent to meet its Sustainable Development Goals, which is a far cry from what we see here.”